Artist Statement

I am a muse gone wild, creating to share myself with others on my terms after decades of assisting others, an enthusiast bringing old-world classicism, and traditional folk-art techniques, glamour, storytelling, detail, and sensuality to the bespoke art I create.

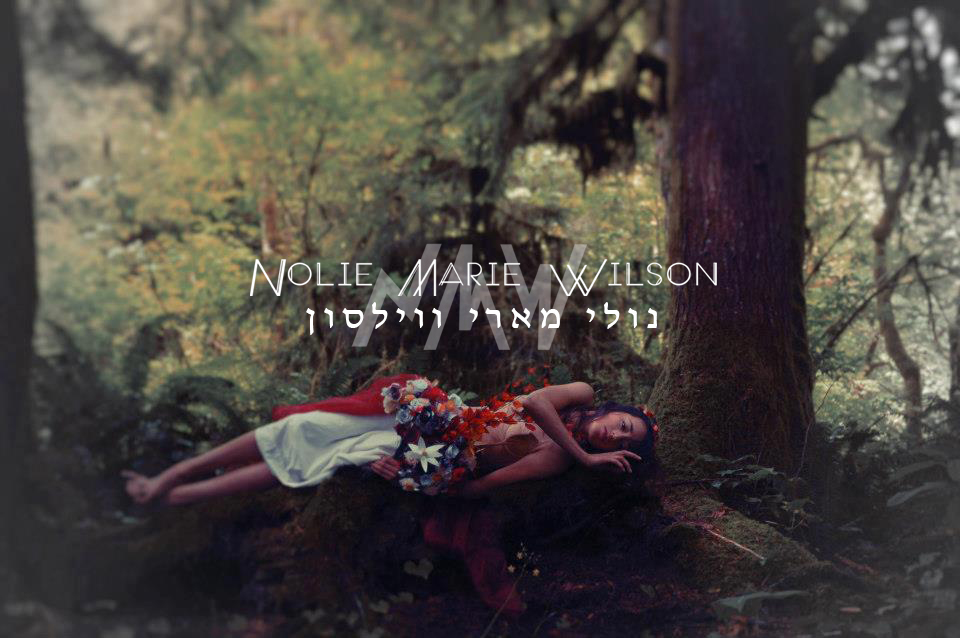

Nolie Wilson

The thing about manic pixie dream girls and muses is that they’re usually pretty smart in our own regard–and a lifetime spent playing second fiddle to cis men leaves one with diverse skills, genre-transcending ways of combining them, and an ability to step gender roles when creating; on closed sets, one cannot wait for a big sturdy cis man to pick up the lighting umbrella, if one is trying to learn how the lighting works, and is helping the photographer. Combine that with a childhood spent learning art and the performing arts to avoid both religious fundamentalists among fellow homeschooling families, and integrating too fully into mainstream secular society, due to moderately fundamentalist beliefs among Nolie’s family, and Nolie emerged from their unique career with opportunities to be mentored, having learned techniques to create a wide variety of “feels” to their work. Yet at the end of the day, someone else would walk away with the right to make money from images Nolie creative directed, provided wardrobe for, executed posing for, helped with as a photography assistant, and did everything but hit the button on the camera for. The historic devaluing of people who participate in the act of creation, without being the legally defined “creator” has made it hard to elevate AFAB artists–as Nolie themself knows, with some professional credits spread under their unmarried name, under their married name, and under professional pennames. But the difficulty of bragging on one resume does not undermine the pride in Nolie’s accomplishments… or the fact that if not for these societal factors, it would be easier to speak publicly about the role Nolie has played in many male artists’ work, as well as about the prominence of Nolie’s own work, subsequently, especially in conjunction with Nolie’s professional credits as a New York Times bestselling romance author, speculative fiction anthology co-editor, scifi/fantasy/romance/memoir editor, whose work reaches all the way to the moon.

Nolie’s ethos of creating as independently as possible, creating intimate pieces that create insightful connections with the audience, extends to their bespoke work, which offers unique storytelling and insights resulting from careful research and attention to detail in assessing their clients’ needs, story, and the purpose and limitations of the prospective piece(s) being commissioned. From Nolie’s earliest days arranging displays of AIDS Quilt segments for Scout awards, because of their interest in helping amplify others’ stories, and preserve them in history, and the time they spent listening to their grandmother talk about the family’s Ashkenazi history, how the family experienced the harrowing global environment during the Holocaust–both those who did, and those who didn’t, Nolie has known since childhood that who shares the story, or creates the final artwork matters. And as a disabled person used to adapting their career goals to their symptoms, capitalist prospects (generally few), and the stigma around the careers they can access, Nolie knows that part of breaking free and creating for oneself is advocating for oneself. for the value of one’s experiences, identities, perspectives, in making one’s work within an artform unique. Nolie’s pysanky rarely replicates existing traditional patterns unless commissioned; but it does introduce into the traditional repertoire ways of adding modern themes, such as Pride Rainbows, film reals and sound waves, visual puns, etc.

One of Nolie’s deepest sources of inspiration in deciding what symbols to use, or what to depict, especially when working with clients or creating historically themed work such as their Mask Up series, designed to look like the face masks worn during the Covid 19 Pandemic, is the concept of the “Shehechiyanu Moment”. To those raised outside Judaism, perhaps this can be understood as akin to the Butterfly Effect, or the concept of Fate–the idea that there is a divine plan making things a specific way, and if you change even a minor thing, it causes a cascade of changes, so everything we experience is the result of a specific intention and series of events. However, the Shehechiyanu is a bit different; it is a piece of liturgy that specifically seeks to build a space, even for a moment, to appreciate the weight of every twist and turn of “fate” that would have to happen to contribute to one experiencing this “new” thing. It is not the platitude told to sick people of, “g-d has a plan for you,” that does not bring comfort to them fro how much pain they are in. It is closer to, “Yes, it hurts, but think through everything it took for this to happen; your grandmother had to immigrate, your parents had to meet, you had to transfer colleges and move cross country, and all of those were good things. You had to give up this other dream; and begin to get the experience you now use to find rewarding experiences counseling others in that position. And you know that of the other things that contributed, plenty more have been good. So much good has come with the bad like this, that even if it is bad, it is still new, and it is still worth appreciating that the hurt of the bad comes also with the choices you made to bring this much good and new with it, and the choices your ancestors made to do the same. So long as you look for the new, the unique, you will always find places to feel safe, and hopeful, or to find the world mysterious instead of dour.” It lightens Nolie’s spiritual load greatly working with clients, and discovering Shehechiyanu moments within their lives that translate to pysanky symbols, storytelling within art, and other kinds of motifs that can render a sense of mystery, importance, clarity, intimacy, or just being seen to the individual or family procuring the art. Whether it’s a couple seeking floral arrangements made from the public transportation maps of the area they first met and lived, the music they first danced to, and their parents did too, or someone commissioning preservation of an heirloom that had fallen and shattered, by embedding its pieces in resin jewelry, it is Nolie’s sense of value and newness in the lessons of history, even intimate family history, that gives Nolie’s work its wonder and edge.

When we mourn Jewish people taken from us too unjustly–generally martyred by antisemites or bigots, we say “May their memories be a revolution;” instead of the usual “May their memory be a blessing.” This is the spirit of my art: embracing fragility, loss, tradition, identity, the weight of history, and our fullest sense of self, even in times of change and loss, in order to feel our fullest sense of hope and kinship. When I create, I say, “May my memories be a revolution.” I explore my own ‘Shehechiyanu moments’ (moments of great spiritual significance, where you find purpose, spiritual intimacy, and even kinship with one’s ancestors, from one’s sense of adventure in and reverence for the new, as one experiences it), and seek them out in the lives of my clients’ families too. It is my hope that when people look at my art, they see their story told, too.

Nolie Marie Wilson