Recent News

Read the latest news and stories.

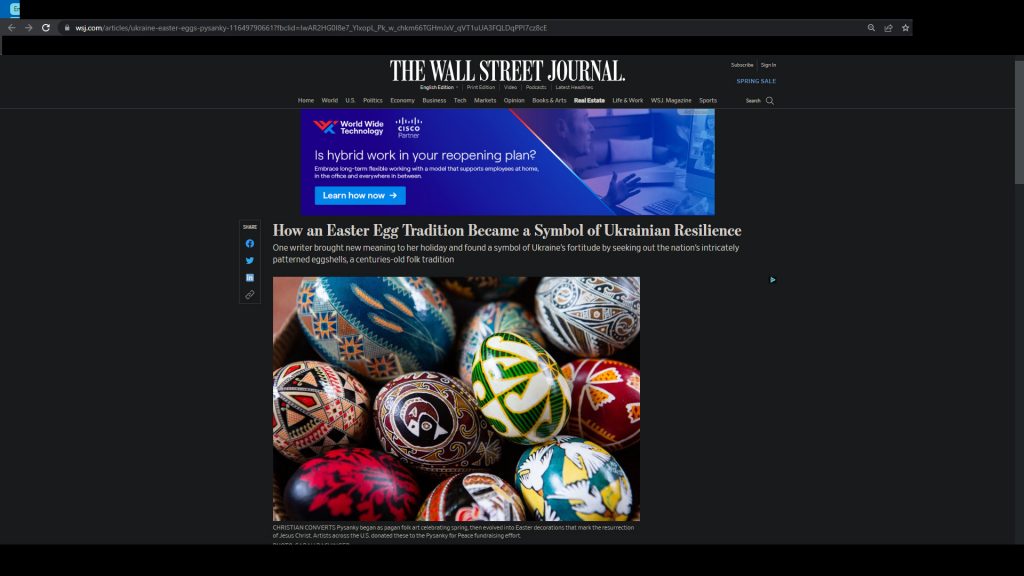

Pysanky for Peace in the WSJ!

Every Republican in my family would be so proud, I think, to see my art in a “legitimate” publication, for once. I laugh, but when this is the stuff of disownments, you have to chuckle, to get past the awareness you have spent your life walking on eggshells, no pun intended. And that there is a special kick from recognizing that you can truly process what success, pride, accountability, and respect mean to you, when you realize that other people’s respect is usually an offshoot of doing what is necessary to respect yourself… and when the two aren’t coming together, it’s usually a sign that something’s wrong. Realizing that even having art on display in the WSJ will not fix a rift with a loved one because they respect it–but will never respect me–is part of the hardship of loving those flawed people.

Perhaps it’s silly to share both the good and the bad of such Shehechiyanu moments as this–perhaps it seems ungrateful to share the downside of a moment when I am witnessing decades of work lead to a truly one of a kind recognition. But so much of my work is tied to community, to family. I truly find value in recognizing that the most valuable healing comes from freeing yourself to feel every emotion you are stuck on–not just the good or the bad, but both. Too often, being estranged, we can find ourselves hung up on one or the other. We are hurt, so we cannot linger on the loving moments, without feeling it devalues our pain the way they tried to, when they refused to apologize. We love them, so we cannot let ourselves admit they hurt us as deeply as they did, because if we do, we must admit that sometimes love is more fair and kind to us when we love people from a distance and do not allow them into our lives.

I live openly about this stuff, when I can, because something like 1 in 4 Americans now have at least one relationship with a loved one that is in estrangement territory–a loved one we do not speak to, or seek to limit having access to our lives. People who are not allowed to have a working phone number, or intimate social media channel. Who will never know our kids, or visit our families. We are told we don’t love them, but that couldn’t be further from the truth, much of a time. Love does not require proximity, and it does not require access and two-way dealings. Loves is a feeling that exists, whether we interact with the person we feel it toward or not. I have borne my scars from these misunderstandings for far longer than this trend has been tracked, and it is often my hope that I can be helpful in talking to other people about it–helping other people learn what boundaries can look like for them, or how to process the complexity of feelings, both good and bad, whether it’s through art honoring all aspects of the relationships and history, or whether it’s through the supportiveness of my dealings with a client who may have a story as nuanced as my own.

In the big burst of publicity around Pysanky for Peace (Yay, Sarah Bachinger, you are a true magician, and a mensch), I was in the hospital. I was in a coma, medically unexplained, but not expected to wake up. After several days I did. And watching the publicity make its way to me, feeling as though I had woken up a la Twin Peaks or Silent Hill in some nightmare world where everything was just different enough to confound me as I recovered, where even the news was distorted by shocking press coverage of unthinkable achievements that should be a tip-off I’m still dreaming, or terror-stricken reports of how the next generations of people will find themselves without the opportunity to protect their health as I did, when I built my health care around the necessity of birth control, abortions, and avoiding a likely fatal pregnancy, given my medical condition… it made for a nightmarish recovery that often left me feeling like I could not tell the difference between I was awake or asleep, because daily life seemed so surreally unreal. And part of it was knowing the unthinkable awfulness of neither the good nor the bad making its way to my estranged family. Not the news that my partner had withheld, knowing my wishes well, that for days, he had thought they had lost their child, as the hospital staff believed too, nor the news that I had awoken and begun recovering eithe. It took me a while to even taking steps back toward my path of updating this website, sending out projects, as I could, without being able to stand, sit, see, etc. for a number of days. But I did not talk much about it, in large part because the hard part about being estranged is that you hesitate to publicly share your joys or hurts, because often, our own relatives are our stalkers, seeking out our professional lives so that they can seek a feigned sense of closeness through nonconsensual updates that those we do wish to be in contact with receive. My spotty communnication on public channels is generally due to this, me having a profound discomfort with sharing information publicly, after repeated incidents of being stalked through my professional interactions. But the fact is, you cannot be in a creative field if you are truly afraid of sharing yourself. All of us artists, writers, dreamers, our work calls to people precisely because it offers a piece of ourselves, that people can view, even if they do not even know our names. This is why people have latched so heavily to social media, and the idea of knowing the artists whose labors they consume as people, not as professionals who cater to their needs. It is a complicated landscape in which to operate as a domestic violence survivor. It is complicated as a creator, when one of the dearest pieces of my heart in my work is that moment when I reach someone, when a piece of my heart in my work finds an unexpected connection with someone who had not expected to be touched so deeply. So for that reason, my own PTSD tendency towards closed-offed-ness is something that I continue to fight deeply against, because after a decade as an indie author, and having spent my entire adult career in creative professions in between the day jobs hating my disabilities, or religious culture, or whatever their problem with me du jour is, I have come to realize that one of the most precious things that I access as a creator, and as someone talking about how my creativity relates to others, is in stating, as often as I can, an d without fail, that you deserve my honesty, because I do not believe that my own struggles are likely to be so different than any of yours, and I do not believe that you deserve to suffer alone, if I might have a chance of saying something kind that provides its own intimate Shehechiyanu moment of kinship for you.

So I truly want to say, for those going through hard times, for those who feel lonely, for those who fear the future… you are not alone. We are all in this together. Interconnectedness is the hallmark of disability, of my life. It’s the hallmark of all of our lives, whether we know it or not. If people can hate without knowing who it truly is they are seeking to destroy, they can love, without truly knowing who they care for, too.

I love you. That is why I create for you.

Hmm. Maybe that should be my real artist statement. It’s probably briefer than my usual too-verbose style of explanation, and it gets to the point.

אני אוהב אותך

I love you.

Thank you, and shalom.

תודה רבה ושלןם

Nolie

נולי

Comments

No Comments