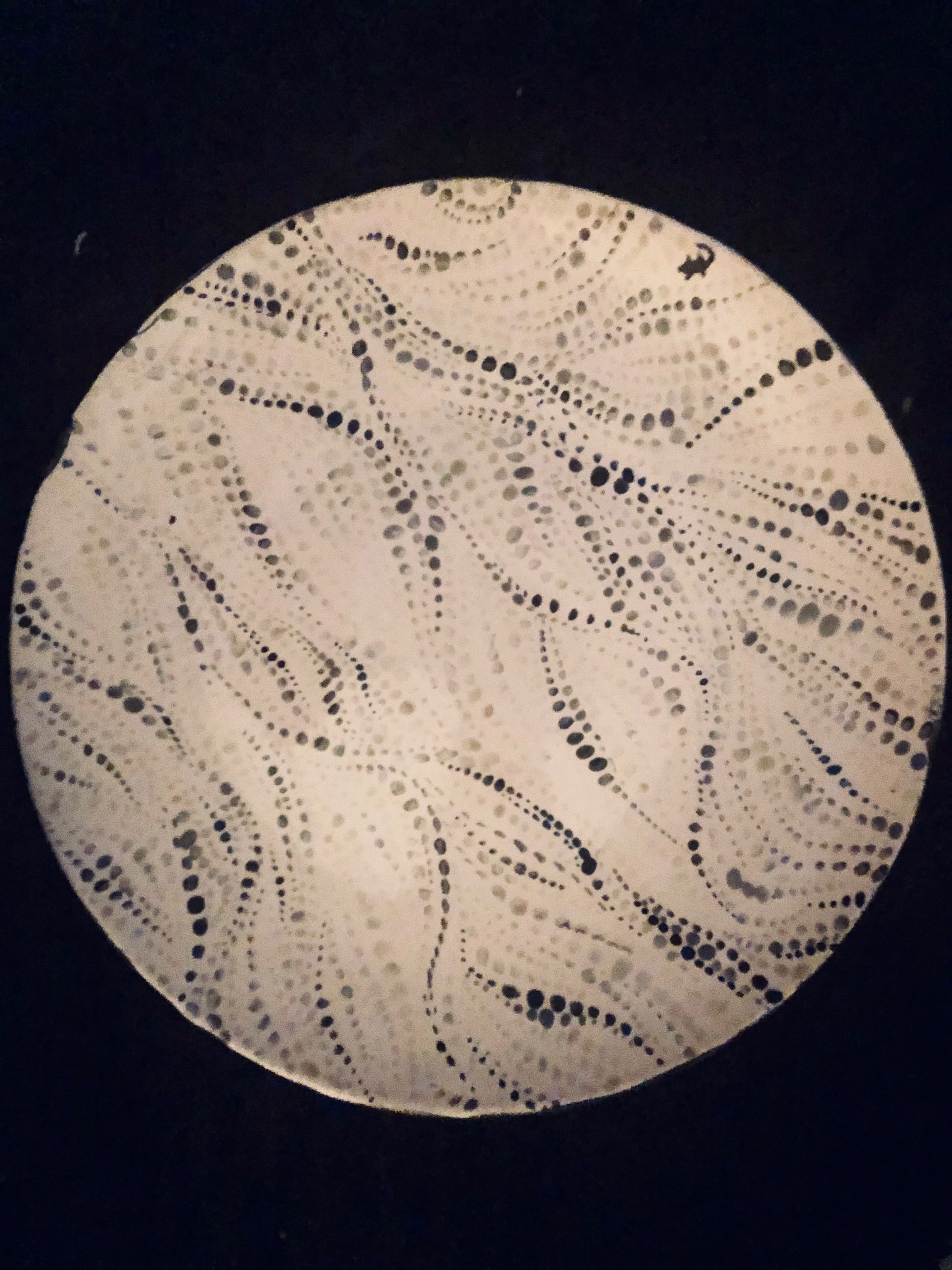

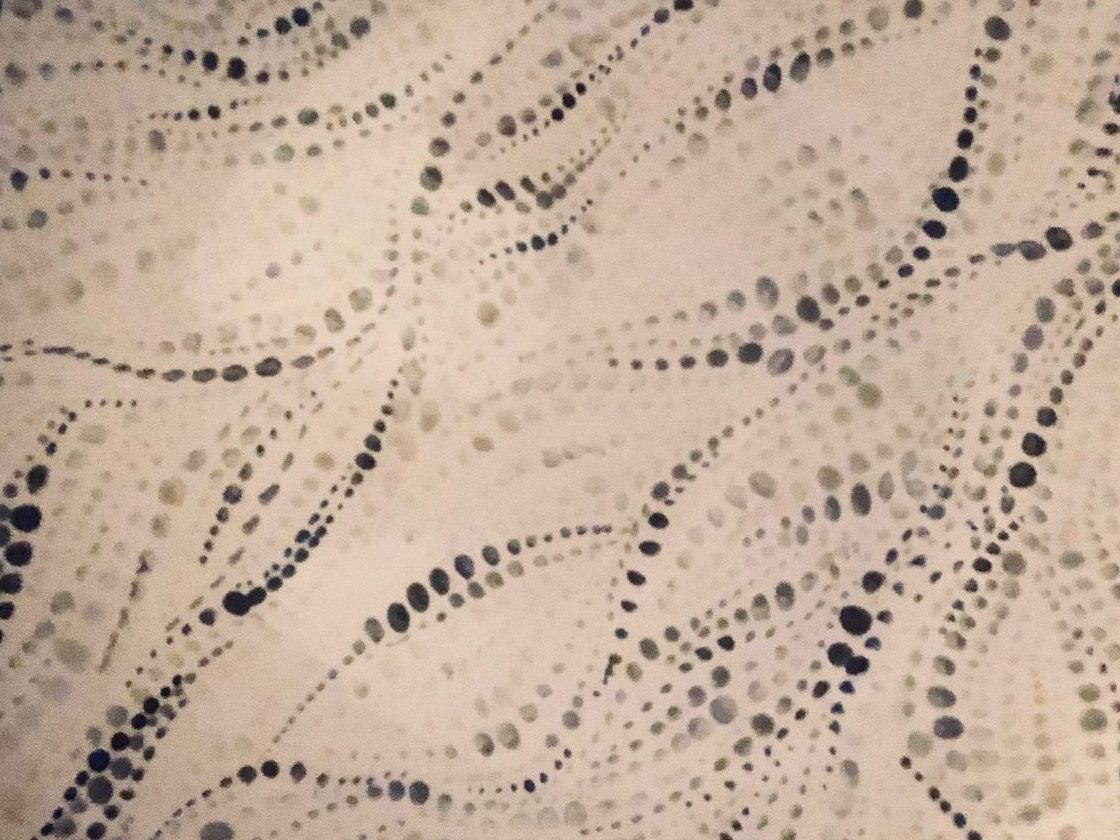

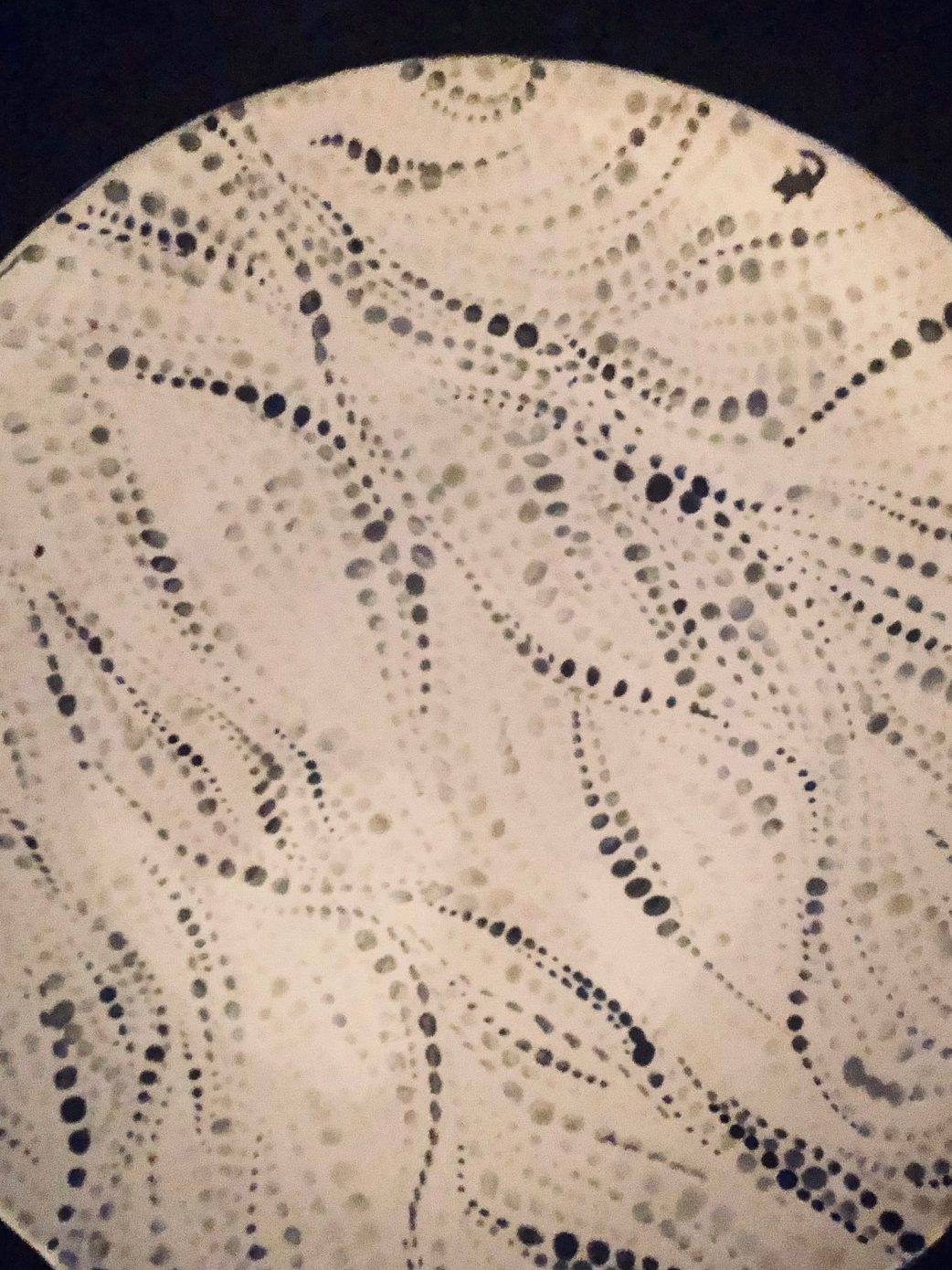

Nolie Marie Wilson grew up painting and sculpting ceramics, even winning awards for their work in organizations such as 4H. A favorite hobby to engage in with their sibling, who enjoyed sculpted figurines, Nolie preferred the challenge of simple, limited canvases that forced them to think creatively about how to build around the space abstractly, or surmount challenges such as idiosyncracies and flaws of firing, sanding, or filing. Plain ceramic plates, flat tiles became the gifts of choice for friends and loved ones, painted as trivets, or intricately designed platters. Photography does not exist of much of Nolie’s earliest work, nor is it available for purchase.

Nolie’s skills in several artistic media: ceramics, acrylic painting, resin casting, alcohol ink dying, pysanky, all merged to create a distinct eye, and a rugged determination to do it themselves, when they could not find pieces of Judaica that were exactly what they envisioned in their home. After sharing images of their rainbow seder plate with friends and getting a positive response, Nolie began writing up tutorials, and photographing their work, in preparation to guide others in how to create their own custom Judaica.

The idea felt particularly meaningful, because of Nolie’s own tormented relationship with the heirloom nature of Judaica. Having grown up with religious coercion to pretend to practice Christianity, and distance themselves from the Jewish practices of their own family members that resonated with them, several of Nolie’s most prized possessions were gifted pieces of Judaica, all that remained of their connection to their family, because of the severity of the fractures in their family. And one by one, each was taken from them- one stolen in a burglary, another vandalized and torn off Nolie’s very doorstep, the month after the Bubbe who gave it to them had died… Both experiences scarred Nolie in different ways; in their 20s, Nolie wore a piercing on their collarbone where the stolen heirloom pendant had hung, before their body rejected it during the development of some of their medical conditions. And the vandalism reminded Nolie of their grandmother’s urgency in fighting to ensure that Nolie never felt anything less than Jewish, and connected to the struggles and history of the Jewish people, regardless of how “Christian” their parents said they had to act.

Coupled with a number of other problematic experiences of antisemitism over the years, in everything from their employment to their closest relationships, that recontextualized that urgency, it became urgent for Nolie, too, to look for a tradition of art in which they, too, could say, “This is what a Jew looks like” as they found opportunities to embrace their heritage: polishing their Hebrew and Yiddish, and embarking on the lifetime journey of traveling with their Jewish extended kin.

Even Nolie’s contributions to the medium of batik eggshells, commonly known as pysanky, an art form often associated with Christianity, is deeply associated with Judaism for Nolie, due to the beitzah, or roasted egg’s significance to Passover, and the necessity of melting wax off the raw egg when preparing pysanky, and the connection between the eggshell’s acid trauma and the meaning and beauty to emerge from how the shell responds to said trauma. The hidden pagan history of pysanky too spoke to Nolie’s own history as one who was kept from their non-Christian heritage and practices, too, and allows them to divorce it entirely from its Christian origins, exploring Jewish versions of the art form, as well as many other similar recontextualizations of the diversity of Jewish art throughout the diaspora. Nolie’s approach to Judaica is thus a reclamation, seeking to explore through folk art, protest art, meditative detail, and a sense of the self through art akin to hiddur mitzvah, a deeply personal, intimate approach to the pieces, as individual heirlooms, ritual objects that can evoke an instant sense of identity.

Nolie’s queerness is deeply connected to their Judaism, to their need for justice and the world to do better, be kinder. Coming from environments of repression and closeting, it is perhaps not surprising that queer themes make it into many of Nolie’s pieces. And it is their hope that incorporating the various colors of LGBTQIA+ umbrella people’s flags into attractive, lush, affordable pieces, may help their fellow queer kindred to feel the presence of their Jewish family around them, whether they are safe to be “out” or not, or whether being “out” has resulted in their expulsion from their traditional family, or a shul with especially exclusionary values. However, they also produce many other colors and themes, allowing for your rainbow to be as subtle as you like.

Nolie specializes in abstract designs, bold blends of color, natural and floral themes, as well as geometric and graphic patterns and controlled asymmetry. This eye for detail has allowed them to create stunning seder plates, hamsas, mezuzahs, and havdalah sets in materials ranging from upcycled glass, to resin. (For more information on the current safety practices regarding resin’s food safety suitability, visit Nolie’s FAQ on Resin Art here. Nolie endeavors to go over and above market practices with regard to food safety, due to their own immunocompromisation lending them a cautious nature.)

Nolie also fulfills custom commissions. If you are interested in obtaining a custom painted or cast piece, please visit our Custom Ordering FAQ.